Having introduced the Artist As Citizen project in my previous post, I plan to use my next couple of entries to explore how, in a free market democracy, individuals and groups acquire beliefs and make choices. How does a free market democracy communicate? What's the difference between being a citizen and being a consumer? How do our personal biographies shape our beliefs?

What are the conditions in which reality is best encountered by the public?

OK -- that's a really big subject, and I figured I'd just do my part to scratch the surface. At the least, I figure, I can relay links to good sources, some of which led to the ideas behind Artist As Citizen. And I've written earlier pieces on a similar theme. I've mulled over ideas on the subject for years, because I direct commercials (so I'm supposed to know something about persuasion) and because, as a resident of Manhattan with an active imagination, let's say historical forces compel me to think about it.

Among recent influences, I just read a very interesting book, Break Through, which contains profound insights about people, behavior, and communication. And I'm grateful for the discovery of some excellent writers online, which leads me to the first topic I'm curious about.

I detect an increasing nervousness among experts about describing climate change to the public. (Specifically, to Americans.) For example, the writers of Break Through take the position that things must be framed in the positive in order to get the public engaged, and the psychological research they use look sound. I think that Break Through gets big things right -- it is good to be positive -- although I think it's also good not to be too cautious and become afraid of consumers, and afraid of voters.

I began thinking about putting my thoughts here by brewing up some tea, promptly getting stuck, and picking up the business section of Monday's NY Times. This at least felt business-like, and it turned out to be surprisingly relevant to communications questions.

On the front of the business section, there was an article about Steven Kirsch, the serial inventor behind the optical mouse, the search company Infoseek, and now a startup company, Abaca, that seeks to banish spam from our lives. The first twist in the article is tragic: this summer, Mr. Kirsch was diagnosed with a rare form of blood cancer. He has responded with an engineer's practicality and determination, and his personal website has a four part to-do list, described in the article, with "Eliminating spam" as number one.

Then, to quote directly from the article:

Fourth on his list is "Why human beings will be extinct in 90 years." He writes, "My incurable blood cancer is minor compared to what is happening with the planet. We have somewhat more than 90 years before humanity is virtually extinct."

It's a mark of the NY Times's poise (or something) that this quirky detail - business leader makes wildly alarming prediction -- doesn't appear until the 13th paragraph in the article, tucked away on the inside page of the print edition. (This reader's mind also raced with thoughts: extinct in 90 years? Climate change the culprit? So...will spam be fixed by then, or what? If Google finds a way to run their servers on solar power, could spam outlive people? Memo to the Times editorial board - as with WMD coverage, all your good stuff is again hidden in the middle of the paper.)

You can read about Mr. Kirsch's dire predictions on climate change here. (Extinction is about a 5% chance, by his count, unless we act. I'm using one of his inventions, an optical mouse, as I write this, by the way.) He writes clearly and passionately, with the single-minded focus of a smart engineer. His analysis of presidential candidates is worth reading too. Some of what he has to say explains why experts are nervous about describing extreme climate scenarios to the public.

Um, I should mention that in his description of the 'worst case scenario' for the coming post-apocalypse generation, the word 'cannibalism' somehow slips in - so I'm pretty sure Mr. Kirsch has broken the strict rules of Break Through, which tells us to focus on hope, not fear, and speak mainly of new opportunities to overcome challenges together (ie, not by eating each other, if that's what you're thinking).

In general I agree with the writers of Break Through - positive messages are better, and in the end may be truer. But as a motivator for my own thinking, I'm very grateful to Mr. Kirsch.

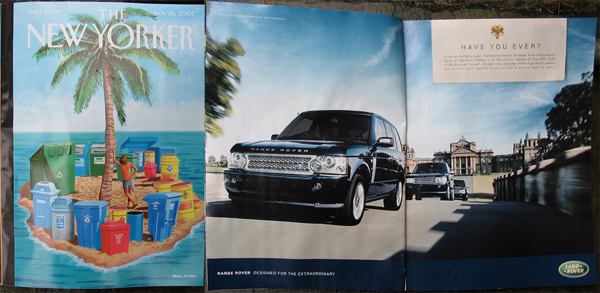

Later the same day, I picked up a recent New Yorker (the 11/26 issue). Idly browsing through it from the front, I noticed pages 6 and 7 are a double-page spread for Range Rover.

The placement and content of the ad, for a gas guzzling SUV, are really interesting. Just as a quick take, this ad seems like an open, in-your-face bet by the automaker that journalism is powerless in the face of marketing (maybe a $ 250,000 bet, considering the cost of the production and ad space). And the ad is aimed at the same valuable, wealthy, educated blue-state readers that are likely to have read, or at least held, Elizabeth Kolbert's prize-winning series "The Climate of Man," which detailed the crisis of anthropogenic global warming in 2005 in the same magazine (and became the book, Field Notes from a Catastrophe). Because advertisers want a return on investment, my guess is that the ad works. (By the way, Ms. Kolbert also just wrote a recent book review for the New Yorker about our future with cars.)

After giving this puzzle thought and meditating on Kurt Vonnegut, I think I do have explanation that would explain the appeal of the Range Rover ad and its imperviousness to even the finest journalism. But I'll leave that to the next installment. And besides, Artist As Citizen is more about asking questions than stating answers, on the theory that the question-asking itself is a positive force. To be even more positive, if somewhat outside the bounds of AAC, I will relay in my next post a guess as to three simple communication steps that would immediately help Mr. Kirsch cross problem number four off his list.